A Fresh Poem: "Ripening" (And a Sneak Peek of Something Special)

And, for those who would like, a few words about both of these things.

Dear friend,

I am excited to share some fun things with you in coming weeks here at The Rose Fire, including several excellent guest posts, a longer essay from me on the relationships between poetry, prayer, and attention, and some exciting updates—with an opportunity for some fun preorder bonuses—regarding my forthcoming poetry collection, The Locust Years.

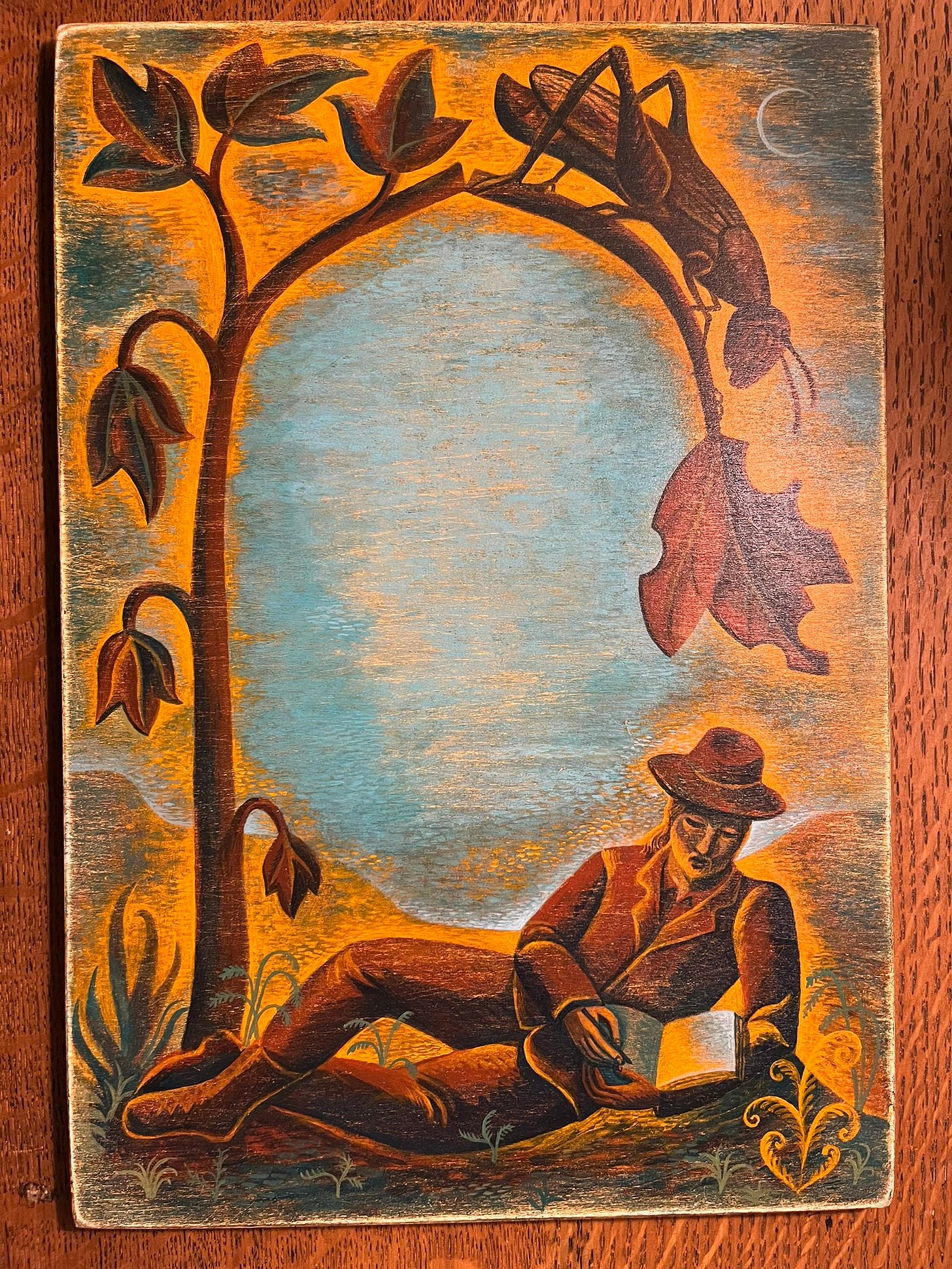

Much more will follow, but I do have an initial tease/sneak peek for you. The brilliant British neo-Romantic artist Michael Cook has been creating the visual world for The Locust Years. (Views of the project in process are available on his Instagram page.) He sent me the painting which will form the cover, which now graces our house. His style perfectly complements my own in this book, and I am absolutely in love with the result. This project will be extremely special, and I can’t wait to share it with you all.

Not the best picture, but you get the gist. It absolutely GLOWS:

In-process (and unfinished) illustrations from the book:

The Locust Years, somewhat like my previous collection, Bower Lodge, takes place in a cohesive world of images that emerges in and between the poems in it. It is very personal for me, but works to elevate personal experience into the simplicity that is found in certain folktales, proverbs, and parables. “There once was a man who owned a vineyard…”, that sort of thing. This is an effect I strive to find in all my writing, and though I often fall short of it, the readers who “get” it report a sense of the words and images following them, of bleeding back in to their lives. This is exactly what I am trying to do: to overlay our world with a narrative filter, a “wisdom” filter, in order to see it as it is meant to be seen. This is the game of life, I think. It is a puzzle, a thing to be interpreted and “read.” My own work is an attempt at that kind of serious play that I think helps us most in learning how to see and read the world, and our place in it.

More on this very soon, with an actual reveal of the final hand-lettered cover, and a chance for you to be the first in line to get the book, along with some fun extras. Exciting!

Now, on to a fresh poem, which you can also hear me read, if you like:

This will *not* be in The Locust Years, but is, in a way, from its “world.”

Ripening

I slept, but I had never seen.

The berries turned from bloom to green.

I found a face inside my head.

The berries turned from green to red.

The face held everything I lack.

The berries turned from red to black.

The face drove me out from the town.

The berries turned from black to brown.

I slept. I saw. I could not stay.

Each berry drops its seeds away.One of the joys of growing as a writer is exploring the various ways in which language can carry meaning. The Postmodernists have tried hard to divorce words from true meaning, and while they seem to me correct in certain regards—particularly in the idea that all words are intended to do things—in their eagerness to tear signifiers and significance apart, they became blind to the most obvious thing about words. Words are never only words. I will not explain what I mean by that here, at least not yet. But to appreciate a poem like this, you must at least implicitly appreciate that when any word is spoken, you are not ever hearing it as a single arbitrary or relative “note.” You are hearing a “chorus”—a “note” (what you think of as the “meaning” of the word), that is attended by a whole host of other “notes.”

These are something like the harmonics of a plucked guitar string. They are in the background. But they are really there. And they are not accidental. The harmonics of a note are determined by physical realities which can be described by math—the length of the string and its frequency of vibration when plucked. The way they are able to come forward and be heard are determined by the ability of the wood to vibrate and the resonance of the instrument. A good musician is able to perfectly tune an individual instrument and play with these physical and mathematic realities rather than against them.

Words have harmonics too. I will try not to over extend this metaphor (I may have already done so), but I do think it is helpful. You likely know already that English is primarily a melding of Germanic Old English with a sort of wobbly French contributed by the Normans, and heavily dependent on Latin. These two main streams each have conributed words with remarkable different harmonics. These have to do with inherent sound, cultural history, literary precedent, and a dozen other things, but you don’t have to think about them to “hear” them. There are overtones; harmonics. The word gloom holds great things in it, far greater things than its “main” meaning. You see that word. It has a temperature, a texture, a feeling. So with brusque. So with lake and leak (which share the same old Germanic root). So with attenuate, or goof, or apple. Each word, in its way, is a chorus. This quality of language is real and meaningful. It is also fun.

In this poem, I worked to select the very simplest words available to me. In that process, I find that the harmonics of each word become, somehow, louder. The sounds emerge, and there is the quality, for me at least, of seeing a very common word like slept as if for the first time. Slept. Slept? Slept! There is a whole world held in there. A whole history? I can sense it. I can expect that you feel at least some of the same key things I do when we say it thoughtfully. It takes on a new sort of strangeness, solidity, and radiance.

I think that “harmonics” of this poem work well. A feeling is created that is predictable, and greater than the superficial meanings of the words. And this is perfect, because the poem is about how things propagate themselves. What (or Who) the Face is at the center of the poem is something for the reader to wrestle. But what the gentle rhyme of it is supposed to do, is capture the sense that there is a life working inside our life—something growing, and ripening, and planting itself by means of the events or choices that we make. The true story, the true work, is not always apparent, even to the one through whom it is being done.

In my experience of life, there is sometimes a feeling that I am berry, or like a berry vine. I am growing according to my place, my nurture, and my nature. I am being, to some degree, what I am and what I must be. I am ripening, through the course of time, toward … what? Each berry drops its seeds away. What a simple line that was when I first wrote it down! But do you, like me, hear it absolutely humming with meanings? I take no credit for it in the least. It is as simple as a nursery rhyme. But boy, it is fun to brush the simplicity and power of even our most basic words like that.

And in that I am reminded how our lives, our stories, are much like our words. They are choruses. They have harmonics.

We can, perhaps only once in a while, learn to hear them.

I love all of this.

Also, happy day after Thanksgiving to you and yours!