A Good Word

Notes Toward a Poetry of Blessing

Dear friend,

I presently find myself in the middle of one of the busiest working months in my memory. My time for personal writing has been unusually constrained. Fortunately, my backstock of unpublished work is decent, and from that vault I lift today’s dispatch. We will return to the core series of essays here at The Rose Fire in due time.

The below essay may raise as many questions as it answers. Its internal logic is not complete, its scope is limited, and I am actively exploring its ideas. For now, I am alright with that. I share it because it outlines a key element of how I think of the function of our language (as a gift that helps us guard and form the world), and of poetry as a particularly distilled and powerful variety of language.

Poetry’s closest relatives are prayer and incantation. The function of blessing, so overlooked in our present culture, is deeply connected to all three of these, down at the very roots of speech and human intention. The point of all this, for me, is to better understand what exactly it is we do with the excercise of creativity, and how such an excercise might be intentionally directed as an act of generosity and self-giving. Blessing, to use another word. It is, in a small way, the object to which I aspire in my own work, and it is helpful at least for me to try to name it a little. I trust that it will also be helpful for you.

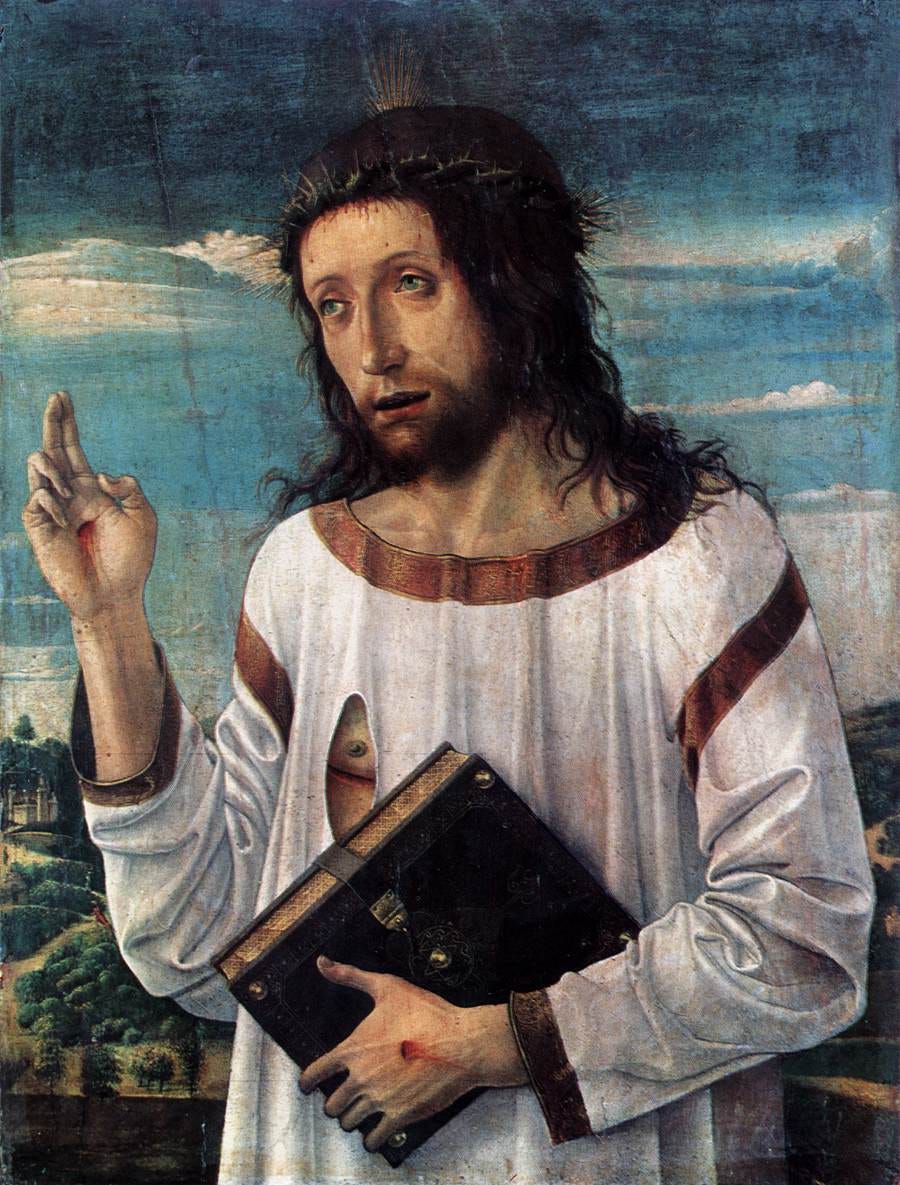

One last thought, prompted by Bellini’s Christ in the image above. That is simply this: it may be true that for both poetry and blessing, our power comes through our wounds.

-Paul

I pledge me to be truthful unto you

Whom I cannot ever stop remembering.

- John Ashbery

One of the gifts of analytic philosophy in the mid-twentieth century was its reminder (primarily via J.L. Austin’s speech act theory) that human communication does things. While postmodern critiques of this led by Jacques Derrida sought to question the nature of language itself, even critiques served to reinforce a central and ancient truth: that every act of communication is an expression of power; that with every word, there is an attempt to do.

This idea of language as an efficacious, quasi-magical thing did not become remote to the Western mind until the Enlightenment. Over countless previous generations, traditions had arisen for the stewardship and governance of this power of language. Druids, bards, shamans, táltosok, medicine men—even the authority of a tribal patriarch such as Isaac or Jacob—the understanding was that when things were said they must be said rightly, or the very order of the world could be threatened. One remembers that medieval miners would not enter their tunnels in the earth without traditional prayers, prayers meant not only to preserve their life, nor solely from superstition, but because they knew that they were delving into the hidden things of nature. They felt their souls, as well as their bodies, were in peril and must be preserved by means of fitting words. (Perhaps their trepidation was preferable to today’s brutal extraction of resources.)

This understanding of language was preserved and sanctified admirably in the Christian liturgy. In the various acts of worship, praise, invocation, and invitation, we are intimately connected to the ancient, animating, and human/divine logic of this most ancient understanding of speech. When a thing is not just said, but spoken under the right conditions, something, usually irreversible, is done. If you care about such things, Biblical precedents are abundant. The world is made ex nihilo by the Word of God. Jacob receives his brother’s blessing through the guile of a bowl of pottage and some goat hair. Balaam, a seer on the steppes of Moab, is hired to curse Israel but finds himself unable to do anything but bless them.

If language generally does, then literature and poetry have long been observed to do a wide variety of specific things. Sir Philip Sidney in his Defense of Poesy argues that the function of the art is twofold: to teach and to delight. Dana Gioia, in Poetry as Enchantment, agrees and goes a bit further: “to delight, instruct, console, and commemorate… to awaken us to a fuller sense of our own humanity,” and surely this is true. But even in these actions, is there something larger being done, something whose exercise elevates the exercise of poetry to an even more intensely valuable spiritual function?

In my view, poetry is uniquely suited to the category of blessing, which can inform, guide, and sharpen our creative practice, and to be extensions of the core work of the human person—to intentionally and skillfully participate in the bearing forth of Beauty.

First, what is blessing, and what does it mean to engage in it? The English word, rooted in the Latin benedicto and the Greek eulogio literally means to speak a “good word.” The underlying term in the Hebrew Bible, barak, contains meanings related to “kneel,” to “praise,” and to “speak life/flourishing.” In all of these cases the sense is of what Fr. Stephen Gauthier terms an “effective word,” a word that does something, and something good. A blessing is not a wish. It is not an encouragement. It is not a feeling, nor the expression of a feeling. Something is caused to happen by means of a full form—the right words spoken by the right person at the right time. A good word.

In the Western tradition, we receive this sense of blessing most overtly from the Judeo-Christian religious background, but it is deeply compatible with the understanding held by nearly all so-called “primitive” cultures, including those in whom the English language finds its oldest roots.

Speech, for the old bards, always did something. The Druids were said to spend twenty years memorizing the verse of their traditional canon, and at the conclusion of their education found that by the virtue of their verse they could discern the pattern of the future from the past, and could thereafter choose any occupation that suited them, and discharge that work with skill.

A blessing is not a wish. It is not an encouragement. It is not a feeling, nor the expression of a feeling. Something is caused to happen by means of a full form—the right words spoken by the right person at the right time. A good word.

Blessing is a central formal act in nearly all traditional and intact cultures. But for the Jewish and Christian traditions it is core to our self-understanding and practice. At the conclusion of nearly every Christian liturgy, the celebrant blesses those gathered with a “benediction”; a blessing in the most direct sense. Blessing returns to us this sense of practical efficacy of language, and the holy power of speech. But it does so with a unique wholeness. Because in blessing, it is, invariably, the good of the other that is primarily sought. One does not bless for an increase in one’s reputation, riches, or any self-serving end. In this, we find that we participate with a unique closeness to the way in which the world is made and remade by the Word.

But what is a blessing? My understanding of blessing involves five elements: spirit (the inward life-power), will (the direction of that life-power to a particular end), goodness (the end willed must be for the flourishing of life, beauty, and wholeness), relationship (one must stand in particular and appropriate relation to the object or objects of blessing), and form (there is particularity in the way of what is said that is specific and fitting for the situation; one does not quote Seinfeld with good vibes toward someone else and say that you have blessed them, even if the quips are crisp and salty).

Rightly done, however imperfectly, the result of blessing is the creation of a sort of spiritual object (which we confusingly also call a “blessing”) that has some sort of objective existence apart from the one speaking it, and is able to effect some sort of real good for its object. For this reason, Jacob was able to, quite literally, “steal” Esau’s blessing from their father Isaac, with no restitution or retraction possible. In that inflexible logic, the blessing had been “sold” for a bowl of pottage, and was subsequently trundled off to Canaan on top of the trickster’s head. (For what it is worth, I have always sympathized with Esau.) Similarly, when Balaam’s intended curse against the hosts of Israel turned itself into an prophetic blessing in his mouth, there was nothing to be done about it afterward, no matter how Balak raged.

A blessing had been made. That was that.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE ROSE FIRE to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.