"Decadence and The Drum-keeper"

An exclusive excerpt from my feature essay for Dappled Things, and a few related thoughts.

Hi, all—today’s dispatch was initially intended to be the third installment of the foundational series for The Rose Fire, which began with The Inconsolable Secret, and continued last Friday with The Hunger of the Dark. But given the complexity and importance of this one, which will be on the purging effect of the beautiful on our souls, I am letting the proverbial tea steep just a little longer.

In its place, here is an exclusive excerpt from a piece I recently wrote for the Eastertide print issue of Dappled Things, one of the foremost Roman Catholic literary and art journals publishing today, and which regularly features some of the most absolutely exciting writers I know. The full essay may be read on their site by clicking here. I also would encourage you to subscribe if you are able.

The essay centers on two things: the concept of cultural decadence as a true “de-cadence,” or a loss of beat, and on Paul Claudel, the French poet, playwright, and diplomat whose ecstatic and psalm-esque poetry, particularly as presented in Jonathan Geltner’s excellent 2020 translation, has something powerful to bring to the conversation.

One of the great challenges of our time—the central problem I am writing against here with The Rose Fire—is to live in proper relationship to Beauty in a time that has not kept or valued its knowledge of it. This relationship is participatory, representing a joyous and perilous invitation to the whole person to “come and see.”

In talking about “decadence,” I am not, I hope, indulging in some self-pleasuring excercise of cultural nostalgia. The point is not to look to the past sheerly for the past’s sake, nor to sentimentalize or idolize it. The point, which I seek first for myself, is to know with humble confidence how our lives and work fit into the larger flow of our places, peoples, faiths, languages, traditions, and crafts. To add our part to it in some small way, and to do so with skill. (As any good musician will tell you, you may be holding the best instrument in the world, but if you can’t play it in time and in tune, it’s better for you to sit the session out.)

Perhaps a good way to think of it is according to the richest traditional theology of the Eucharist, which stresses that the ceremony of thanksgiving and communion does not, strictly speaking, come to us from the past, but is our way of “remembering the future.” What we keep, we keep for all, and so make a gentle mockery of time.

All of this, and more, is held in Claudel, though he could not possibly have foreseen, prior to the World Wars, how much weight his words would gather with the decades.

I hope that you read and enjoy this essay, which represents my attempt to portray some of the importance that rides on our stewardship of our shared gifts, and to put into perspective why it deeply matters that all of us—all of us—join with fresh intention in the common and joyful work of creative expression.

-Paul

Selected excerpts:

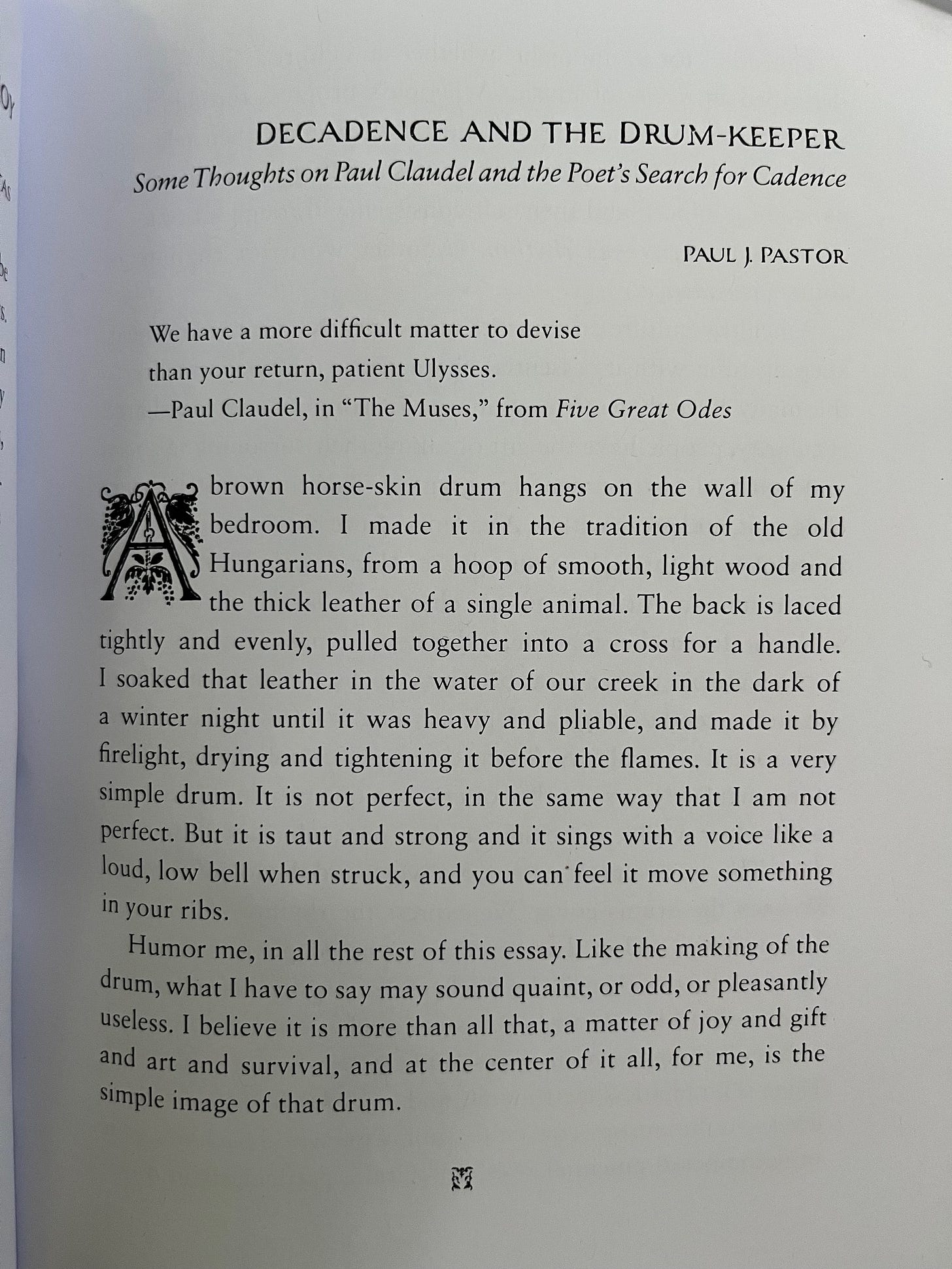

Decadence and the Drum-keeper: Some Thoughts on Paul Claudel and the Poet’s Search for Cadence

We have a more difficult matter to devise

than your return, patient Ulysses.

—Paul Claudel, in “The Muses,” from Five Great OdesA brown horse-skin drum hangs on the wall of my bedroom. I made it in the tradition of the old Hungarians, from a hoop of smooth, light wood and the thick leather of a single animal. The back is laced tightly and evenly, pulled together into a cross for a handle. I soaked that leather in the water of our creek in the dark of a winter night until it was heavy and pliable, and made it by firelight, drying and tightening it before the flames. It is a very simple drum. It is not perfect, in the same way that I am not perfect. But it is taut and strong and it sings with a voice like a loud, low bell when struck, and you can feel it move something in your ribs.

Humor me, in all the rest of this essay. Like the making of the drum, what I have to say may sound quaint, or odd, or pleasantly useless. I believe it is more than all that, a matter of joy and gift and art and survival, and at the center of it all, for me, is the simple image of that drum.

Consider for a moment whether a culture’s life may be described in terms of music. A people’s progress through time might be compared to the rise and fall of melody; their relationship toward other peoples and cultures as harmony (or the dissonance of conflict); and their self-consistency throughout time—a culture’s integrity—as rhythm. (Another word for rhythm, of course, is cadence.)

A healthy culture sustains its music clearly. It moves on-beat, keeping time with its essential character, and giving stability to the many lives that move within it. Trusting in a larger, shared regularity, people have the gift of taking their surrounding social and spiritual environment for granted. They may rest upon it, cling to it, and grow with it. A cadent culture moves with a ragged unity of form through seasons, years, decades, and centuries. Its pace is human. A cadent culture cherishes a larger life that beats within it. It matches that life; it dances and marks time by it.

As centuries pass, a clear beat may be discerned, as the gifts of creation extend through a people learning to know and love them with rooted particularity. A song emerges, rich and lovely because of its singularity: a song that offers a unique people’s unique gift to the wider world, witnessing to their particularities of time and place. This is, to a great extent, the work and the joy of the poet. We keep the drums going. We express the rhythm of this great shared music, and in that expression, the people find that their dance is held together. We keep a beat of authentic life, a beat that holds steady, like a heart, what is essential to our being.But all things have lifespans, and the beat is not guaranteed. There is no faultless metronome, and loss of this cadence—decadence—is the entropy constantly calling the world back to a state of decomposed potential. Western culture, particularly in America, shows many qualities of advancing decadence. The resulting cacophony of “music” is clear at every level of society, from the rise of commonplace vulgarity and violence to the degrading quality of our politics.

In the fine arts, we see the results of a decades-long retreat of true imagination, able to tear down but rarely to build, and covering its impoverished spirit only by means of constant novelty and self-reference. At a time when the Internet could be leading to a golden age of ambitious and powerful new music, poetry, fiction, and cinema, audiences have divided into subgroups of subgroups, losing nearly any shared cultural experience except for franchised media such as the endless regurgitation of franchised entertainment “universes.” The results are unpleasant, confusing, and deafening. In this, the drum-keepers’ work is to try to discern and return to a state of clear, tight cadence.

To do this is not easy. But the contemporary artist or poet, as drum-keeper, is not left alone. We are not the first to face the daunting task of nourishing and advancing a common rhythm; we will not be the last….

From later in the essay:

…A poet keeps the beat. And the beat I am describing is the pulse of a culture’s true and best nature. This can always be described as some variation of a wisdom tradition, which in every intact culture is the domain of poetry and its close cousin, fable. While there are functions (“speech-acts,” to let Derrida briefly in the room) of poetry that are certainly not primarily intended to teach, poetry as a whole has a clear cultural mandate: to gently, skillfully, and often unconsciously both preserve and cultivate a people’s capacity to know truth and beauty. In this way, all poetry fulfills a usually unspoken ethical and cultural mandate: to keep those humans who contact it in touch with goodness.

As the decadence of any lapsing culture proves, keeping the beat is not guaranteed. As with music, a brief lapse of rhythm may happen from time to time and be barely noticeable. Since most cultures keep their time on the scale of centuries, it is only in the ability of a culture to transmit its best qualities across generations that allows an observer (“listening” back through history) to determine what its essential rhythm is, and in what ways it is beautiful, and to what end the whole thing seems to incline.

The state of American poetry over the past half-century mirrors the state of our culture’s shaping forces, creating an often beautiful but supremely inconsistent body of work whose focus is on the primacy of the individual. Here we face a situation that, while far different than Claudel’s, still represents a breakdown of the beat. In our present situation, we could gloss the present canon and imagine that we were seeing the poetic heritage not of one culture, but of hundreds or thousands of individual cultures and subcultures, some of which are clearly limited to a population of one—the poet. While much loveliness can be found throughout the tangle of the contemporary scene, the overall effect is one of complete decadence, in the true and technical sense of that term. To what end do we all beat our individual drums, simultaneously rolling through wildly disparate time signatures? And how could our culture, or any culture, dance to this noise? What are we keeping? In what are we participating? Where is the happy roll and the step of it? In the numbing profusion of beats, our beat has become lost.

Lost, but not because it is gone. Because it has become difficult to discern. For this reason, any poet who takes poetry seriously—not only as a mode of personal expression, but of joyful obligation or cultural service—finds himself or herself faced with a challenge comparatively few of our ancestors had to countenance. Indeed, as I have noted, an argument could be made that Claudel’s generation was one of the first to face it. No longer is it enough today to seek to give voice with freshness, skill, and energy to the best parts of human life. Today we must select what those parts are. To honor any subject, particularity, moment, concept, or tale with our poetic energy is to say to those who choose to be our audience: You ought to look at this; it will be good for you. This is a thing that is beautiful; this is a thing that is true…

Speaking of decadence a now very popular and powerful religiously and culturally illiterate nihilistic barbarian Cult leader is an in-your face prime example of such. I am of course referring to the leader of the MAGA cult. Surprisingly, or perhaps not, he is very popular with many right-wing so called conservative Christians.