"Half a Transport — Half a Trouble"

Isabel Chenot, on the enchanted herbarium of Emily Dickinson

Dear Readers,

I’m pleased to share this guest post from the excellent Isabel Chenot, whose excellent poetry collection, The Joseph Tree, is available from Wiseblood Books. “Wanting to keep flowers is part awe, and part hope,” Isabel writes below. “And it is part pain—part of dignifying everything that has flourished and is gone.”

Reflect with us here on the beautiful eternity that can be held in the withered things.

-Paul

Flowers – Well — if anybody

Can the ecstasy define —

Half a transport — half a trouble —

With which flowers humble men …

-Emily Dickinson, ca. 1859I don't remember when I first met Emily Dickinson. A poem or two of hers has been in my memory for as long as I remember poetry. If she were able to write an introductory paragraph for herself, I do not know that she would tell us that she was born in 1830 and died on May 15, 1886, that she kept house for a chronically ill mother, that only ten of her poems were published in her lifetime, that she came to wander in white alone and to speak to visitors through the door, and even so, was fondly remembered by children—the details that, in a mass of unrecorded lives, have blown away like chaff. When she could write for herself, she told us how the sun rose. She kept that, like she kept flowers, as the grain of her experience.

Perhaps my school-age misgiving about information that seemed to substitute for communion explains why the impression a friend conveyed, of a morbid recluse rustling through crepuscular rooms, was never mine. One of the poems I had memorised, “They might not need me—yet they might” made me feel that Emily Dickinson played with poetry like a kitten with its own tail, and after reading how amiable her relations were with the bee, and imagining her gesture, offering crumbs to a bird—I thought that she must have spent an absorbing amount of time among minute creatures outdoors—even, that she belonged to them.

I accepted her social eccentricity, wandering in white and speaking to visitors through the door, as naturally as I would accept the eccentricity of a hummingbird. It is her poems that have increasingly stunned and bewildered me. How can even words say so much of what we mean? But it has never jarred my sense of the fitness of things that someone who could write with extravagant airiness about flight being “too silver for a seam” could also describe the thud in grief, when we drop through the floor of our mind. Neither of these events is strange to us. Only, Emily could reach into an “Element of Blank” and pull out language. Surely, something so adjacent to God does come at a cost.

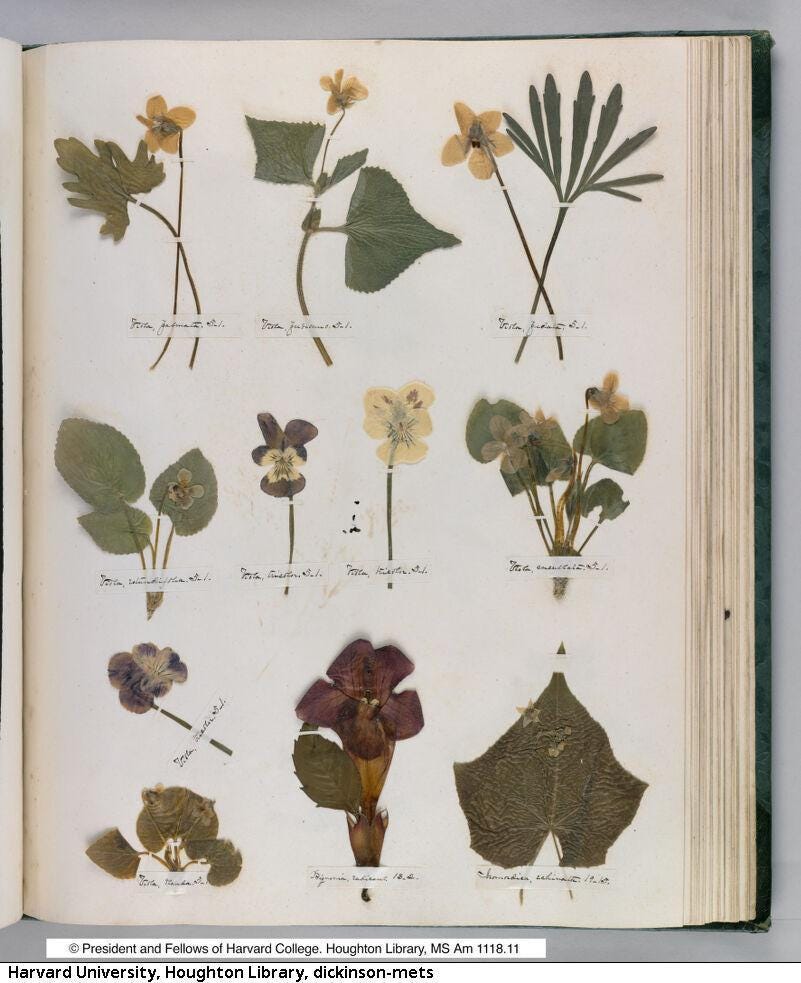

Her herbarium—the collection of plants that she gathered, pressed, and organized—is available to view online via Harvard's Houghton Library. I imagine her sometime between 1839 and 1846, the sunshine in her hair dripping close to the page, while she adjusted a yellow violet (seq. 49).

As I arrange flowers dry on a page for my own herbarium, I think that the “half a trouble” flowers give is the trouble we give a mortician. Or a priest: long ago, it was priests who embalmed the Pharaohs. And Emily did this, too, bent over, tacking down stiff cobwebs of pedicel and leaf.

The violets Emily preserved in her herbarium above have since spanned more of time than Emily did. The labels slashed across their stems have been compared to her trademark em-dash, and every page seems to map some pucker of her soul—lavish, almost fairy whimsy (“Dropped into the Ether Acre —”), electric agility (“Bloom upon the Mountain — stated —”), the slant energy with which she clustered words (“I heard a Fly Buzz — when I died”). Can you feel the closeness of her breath while she bent over the book, in the metrical space between flowers? And something she brought even closer:

That whoso sees this little flower by faith may clear behold the Bobolinks around the throne … (ca. 1859)

For Emily, the streets of eternity were gold with dandelions.

(seq. 46)

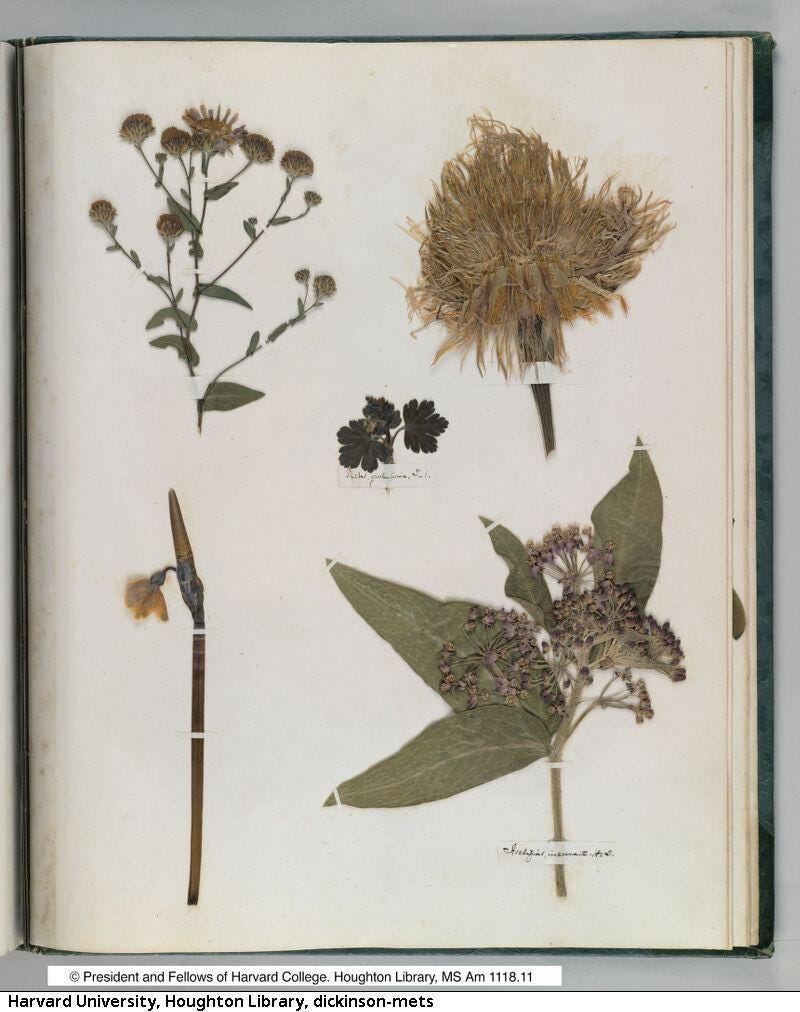

(seq. 66)

Between 1839 and 1846, Emily would have been nine to sixteen years old. It's believed the herbarium was complete by the time she was fourteen. Sixty-six pages, 424 plants—it must have been an eager scientific endeavor. (With a few spelling mistakes.)

Irenaeus said that “what we learn as children grows up with the soul and becomes united to it.” Emily's soul grew up with flowers, and gained a habit of attention. She had a passion to record and keep what she saw. It was a habit of awe: since Adam’s poem about Eve, awe is the purest impulse of poetry.

Maybe more than chronicling local plant specimens in her herbarium, she was hoarding a soul’s gold.

If we could take the train to Fingerbone, Idaho, and find the dictionary from the bookcase in the living room of Marilynne Robinson's Housekeeping—the one in which Lucille and Ruthie were trying to look up “pinking shears.” If we flip to H, we might open to a dried hydrangea. Or a hyacinth. Ruthie flipped to P, and found pansies. “They were flat and stiff and dry—as rigid as butterfly wings, but much more fragile.”

Nudging such delicate tissue aside, at “herbarium” we would read something like: “A collection of dried plants systematically arranged; a hortus siccus. Also, a book or case contrived for keeping such a collection; the room or building in which it is kept.” (Taken from my two volume Oxford English Dictionary, deciphered through a magnifying glass, beside some drying hibiscus.) So much for the sense of the word; but what about the flowers? What is the sense of dried flowers?

Ruthie and Lucille had that conversation:

“What will we do with these flowers?” (Ruthie)

“Put them in the stove.” (Lucille)

“Why do that?”

“What are they good for?”

Lucille crushes the flowers to dust, and with it, the sisters’ fragile attachment to one another.

Dust is what we all crush to eventually. Our ancestors told stories about waking from dust, their fresh lungs filled with God’s breath: it was in a garden. God walked with Adam there. And Adam composed that poem to Eve.

There was a garden near the cross, where they laid Christ:

Primrose, anemone, bluebell, moss

Grow in the kingdom of the cross.

And the ash-tree's purple bud

dresses the spear that shed his blood.

-Kathleen Raine, “Lenten Flowers”

A garden full of silence of dew,

Beside a virgin cave and entrance stone:

Surely a garden full of Angels, too,

Wondering, on watch, alone.

-Christina Rossetti, “Easter Even”In a garden, God comforted a grieving woman.

Our frame is dust; our days are like grass. As a flower of the field, we flourish – a wind passes over and we're gone and the place we filled holds no memory of us (Psalm 103:15,16). Dried flowers are a way to remember our place. “For in each flower the secret lies of the tree that crucifies” (Raine).

Wanting to keep flowers is part awe, and part hope. And it is part pain—part of dignifying everything that has flourished and is gone.

The whole mystery of ourselves is in a garden. Wanting to keep flowers is part awe, and part hope. And it is part pain—part of dignifying everything that has flourished and is gone.

After I saw Emily's herbarium, I had to make one (pictured below). Because more than I hope to tell another soul the year that I was born—I want to say what Emily's flowers said to me, after a friend introduced us. What did they say? That all of us are born. That we die. And in between, we drop through the floor of our minds with grief. But all the desolations of almost two centuries of intervening years do not discredit a dandelion.

I feel smaller, looking at the exquisite spume of fields that were in bloom nearly two centuries ago. Unmoored from my bearings on transience and adrift in the beauty of our place.

Emily's herbarium is too precarious with antiquity to handle. But I can't help hoping the pages I've sewed together will be touched for many years. However strange the future is, human beings will still be fragile. There will still be addiction, broken promises, neglected and orphaned children: we drag such things after us from birth, like death on a string.

I hope fingers like mine will still pull toward small, tangible things, and that someone yet to be born will leave fingerprints on the foxtail. Like a wanderer who feels a texture from home, I hope his or her fingertips wake to Eden. Ruth Pitter wrote that “violets grow in a lost kingdom where no creature mourns” (“The Tuft of Violets”), and Emily was not wrong about the streets of gold. When all of us come home, there will be masses of yellow violets. We will “arrive where we started, and know the place for the first time” (Eliot, “Little Gidding”).

Flowers have to be pressed dry three to four weeks before mounting. I'm afraid I tend to be too liberal with glue; but mounting flowers is a good way to let your thoughts sink down, and watch which ones resurface.

Something that resurfaces lately is about how flowers I've pressed dry between obsolete words in the Oxford English Dictionary will never make more flowers. Any signal they carry across time comes at the cost of their desiccation. A flower’s fertility only clings to the margins of oblivion by embracing oblivion. It forms a seed not by being kept, but by withering, and going out.

Whose are the little beds, I asked

Which in the valleys lie?

Some shook their heads, and others smiled —

And no one made reply.

(ca. 1859)I have a note in my journal: Let yourself go out. Isaiah says that grass withers and flowers fall—but God's word rises forever (Isaiah 40:8). The genealogy in Matthew records fourteen generations between Abraham and David, and fourteen between David and the captivity, and fourteen between the captivity and Christ—but we have no genealogy of flowers. We have only the flowers.

Christ bends over the book. And he has all of time to keep a promise – while we have only a handful of years to notice, and cling to his work. Blinkered by birth and by death, we see so little of what he is doing with us, with our loved ones, with our efforts, our prayers—we see almost nothing.

But we still see the flowers. We see their cadence on the page.

Isabel Chenot has loved, memorised, and practiced poetry all her remembered life. Her writing has appeared recently in Orchards, Mere Orthodoxy, Voegelin View, Amethyst, Snakeskin, Story Warren, Vita Poetica, and Ekstasis. Some of her poems are collected in The Joseph Tree, available from Wiseblood books. She just added a dwarf poinciana to her garden.

Poems referenced (or relevant to the) above, by Emily Dickinson:

They might not need me – yet they might –

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

Pain – has an Element of Blank –

Bloom upon the Mountain – stated –

I heard a Fly buzz – when I died –

We should not mind so small a flower

Whose are the little beds, I asked

– These can be searched for and viewed in her handwriting at the Emily Dickinson Archive.

As I read your lovely essay, I looked over at my poor gladiolas in a vase. Only the ones left at the very top are still vibrant and time is taking them away one by one. Thank you for your insights on this important topic. I mean that very seriously. And for sharing Emily's herbarium - what a resource! - and your own. (So many associations...dried flowers falling out of old Bibles. Not long ago, I dried roses and yarrow in a vase but they reminded me of Miss Havisham in Great Expectations.) I will certainly remember your essay and especially this quote as summer passes: "Wanting to keep flowers is part awe, part hope. And it is part pain - part of dignifying everything that has flourished and has gone."

Beautiful essay! :)