Dear Friend,

Spring has come to Oregon, where the new growth is shooting up from the roses and the lilacs, and the light takes on that curious April warmth that is still just a little thin on the electric green of the old moss and the new grass. I know the morel mushrooms are popping up in their secret little villages, but have not found any yet this year. (I have not had much time to get out to really look, though.)

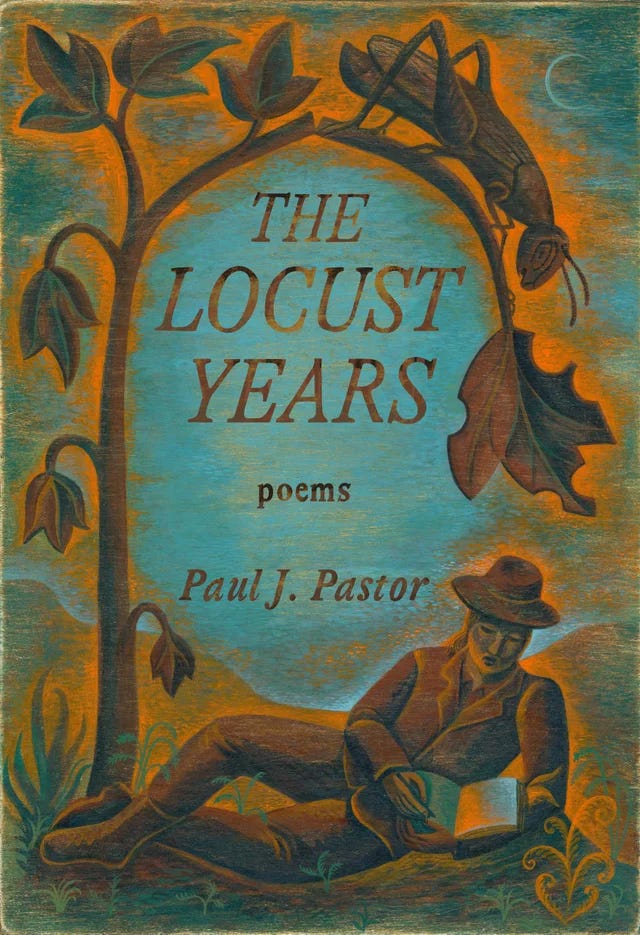

Review copies (Advance Reader Copies = ARCs in book lingo) of The Locust Years have been going out to reviewers and interviewers. We have had enthusiastic response, and I am humbled by the strong interest people are showing in the book. I can’t wait for you to read it, and expect that you’ll be fully tired of hearing me talk about it by the end of the Summer. Of course please preorder if you haven’t had a chance yet, in either the single hardcover or the hardcover bonus package options. If you would like to help and are connected to a strategic way to get the word out about the book (defined as MOSTLY but not EXCLUSIVELY either traditional media or larger podcasts/Substacks), feel free to contact me with any ideas you have about how to do that. In general, some ideas that anyone can do to help the book get out there include:

Plan to read it with others—perhaps as a Summer or Fall book group? (It is arranged seasonally, and has plenty of “scope for the imagination.” Or discussion.)

Give a copy to someone who might enjoy it. (Perhaps pair with a handmade mug from a thrift store and some coffee or tea to give a moment of slightly unhinged beauty to your friends or relations?)

Suggest it to your favorite publication or podcast for review or other ways to share.

Write a review of your own online (Goodreads tends to be best.) Yes, people really do read those as they find new books!

Thanks to all of you for your encouragement and kindness. I can’t wait to share this work with you.

NOW, on to the real fun. For today’s guest post below, I’m pleased to welcome Mary Grace Mangano to The Rose Fire. Mary Grace, a poet and critic whose work you should watch, is a writer and professor living in New Jersey, whom I first met through the Master of Fine Arts program at the University of St. Thomas in Houston. She writes here on that most absolutely inconvenient of good follies, both in life and creativity—trying to follow what one loves.

Enjoy,

Paul

I loved reading and writing from a very young age. I remember being in middle school, waking up early before the rest of my family when the house was quiet. I would get dressed in my school uniform, then sit with my back against the wall, close to the radiator, which would make my wool socks even warmer, and I’d read as long as I could before I was called to breakfast.

That love is what convinced me, ultimately, to study English in college, even after some confusing discouragement from teachers who told me I could do more than “just teach” after graduation and tried to steer me towards a communications or marketing degree. I didn’t know what I would do with an English degree necessarily (and eventually, I would “just teach”), but I wanted to study great literature and to write. And so, I declared myself an English major.

It would seem I am part of a dying breed. In the past two years, The New Yorker and The Atlantic have featured articles about the “End of the English Major” and declining literacy rates among college students. The New Yorker piece cites that, at one Ivy league university, “English majors fell from ten per cent to five per cent of graduates between 2002 and 2020, while the ranks of computer-science majors strengthened.” On one level, I understand why more students are choosing disciplines outside of the humanities. I believe this is what my own high school teachers were trying to do for me when they suggested marketing; they were trying to encourage me to choose something that would be more, well, marketable, with less risk and greater chance of (financial) reward.

A lot of our culture is designed to minimize risk. “Thirty days or your money back!” “Satisfaction guaranteed.” “Free returns”—and you don’t even have to package it yourself. There’s no risk at all. Either you love what you bought and keep it, or it goes back, as if it never happened and your money is returned to you.

The thing is, though, life isn’t like this. Love isn’t like this. Love involves risk. Most things worth attempting require some measure of bravery. Perhaps even some measure of foolishness and the possibility of loss.

A lot of our culture is designed to minimize risk…

The thing is, though, life isn’t like this. Love isn’t like this.

In his essay, “Learning to Live,” Thomas Merton says,

The function of the university is, then, first of all to help the student to discover himself: to recognize himself, and to identify who it is that chooses.

“Who it is that chooses…” I knew I made the right choice in studying English because, as Merton says, I recognized myself more. I became more myself the more I studied literature and writing. Merton goes on to say that the university, like a monastery, should help a student arrive at a point of “spiritual nakedness” where

you become free not to kill, not to exploit, not to destroy, not to compete, because you are no longer afraid of death or the devil or poverty or failure.

Even if I was dying, or poor, I would still want to read and to write. Studying English was not about what it could get me, but what it could give me: myself.

Merton cautions against education that confuses means with ends. His advice is to avoid success because it makes it harder to distinguish “who it is that chooses” and may mean losing one’s true freedom. There are no guarantees of “reward” in this life. The only certainty is the reality of death, loss, and failure. Knowing that these are certain to be faced in life, what will I freely choose to do? How will I live?

All of us are dying, anyway. Satisfaction and material wealth are not guaranteed. Should they come, they are not even guaranteed to make me happy. There are plenty of examples of the unhappy rich. We must ask, why? Beyond simply providing for ourselves and those under our care, why do we do what we do? Like my own pull toward English, shouldn’t our best bet in life be to follow what we love?

But to do this, of course, is to risk. It is to risk everything. In love, we put our very lives on the line. There are no returns. Not really. We may want money-back guarantees, but real life is better than that. Real life is risky and uncertain, mysterious and beautiful.

In 2006, some students at Xavier High School in New York City asked the writer Kurt Vonnegut to visit their school to offer his advice. Citing that he was older and no longer liked to travel, he declined the offer but wrote them a letter. He told them to practice any art; it didn’t matter if they did it very well or badly, but he emphasized not to do it to get money and fame, but to “experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.” He ended the letter with an assignment. He instructed them to

Write a six-line poem, about anything, but rhymed. No fair tennis without a net. Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. […] Tear it up into teeny-weeny pieces and discard them into widely separated trash receptacles. You will find that you have already been gloriously rewarded for your poem. You have experienced becoming, learned a lot more about what’s inside you, and you have made your soul grow.

This is truly the reward we seek when we seek anything: to receive ourselves, to offer ourselves, to make our souls grow. Like Vonnegut, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote his Letter to a Young Poet to a nineteen-year-old Franz Xaver Kappus—not much older than those students in New York City. In one of his letters to Kappus, Rilke implores, “Ask yourself why you do this thing you call writing. Look and see if its roots draw from the deepest place in your heart. Ask yourself if you would die if you were forbidden to write. Above all, ask yourself in the stillest hour of the night, Must I do this? […] If you respond to this question with a strong and simple yes, then build your life according to this necessity. Your life, in its most ordinary details, should bear witness to this imperative.”

Why study English? Why write? Why follow Jesus? As Merton discussed in his essay, freedom is when we know who it is that chooses in our lives. Who is choosing to do these things? And why? In The Glory of the Lord, the Swiss theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar said that the Christian life is a form, a way of existence. It ought to shape a person’s life the way that Rilke discusses building a life around writing, if it is a “necessity” for that person. If I freely choose to write, to be a Christian—not because I hope for some reward from these choices now, but I do them even amid poverty, suffering, and failure—these give a form to my life, seen in the most ordinary details.

In Matthew 16: 1-4, the religious leaders of the day want Jesus to give them a “sign” from heaven. They want a guarantee. Jesus, who has been doing miracles for the poor, infirm, and downtrodden, in this case refuses to “perform.” He does not grant this request, which is not from faith at all, but quite the opposite.

I’ve sometimes encountered people who seem like they want to “sell” faith. Being religious makes you live longer. You’ll be healthier! Happier! Maybe those statistics are real. But I don’t think that they are any sort of reason to have faith. Jesus is not a vitamin. Maybe, from certain perspectives, my life will even appear to get worse by giving my time or attention to religion, or to English, or to writing, or to any of the things that I love. That is okay. Because that risk is the price of love, and love is the point of life.

The lives of the saints, many of whom were martyred in some of the worst ways imaginable, shows us the cost of love like that. The lives of many great writers and artists (Hopkins, Dickinson, Van Gogh) show the same lesson. Real love can be immensely complicating to our “success.” But it is also the only path to true success. How many “successful” people ended their lives in outward glory and inward shame and regret? How many saints went singing to their deaths? How would my life look different if I sought to be loving rather than successful?

Real love can be immensely complicating to our “success.” But it is also the only path to true success.

If I am possessed by love, if “Christ is in me,” if I am free—how would I live? What would flow from me? I would do what I love and be on fire to share that with others. If I noticed something beautiful, or heartbreaking, I would draw others’ attention to this, too. My life would be shaped by this love, seen in all the ordinary details of my days. I would fail at it constantly, of course.

In Mystery and Manners, Flannery O’Connor explains, “To the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” Sometimes, we need to exaggerate things for people to pay attention. In their various forms of artwork, Picasso and Modigliani and Van Gogh did this—they distorted something or drew attention to one aspect of a flower or a person to make us really see something about it. The Mass does this in many ways—incense, bells, vestments, our physical postures—all to remind us that something miraculous and mysterious and out-of-the-ordinary is happening, even if, to our eyes, what’s before us still appears as bread and wine.

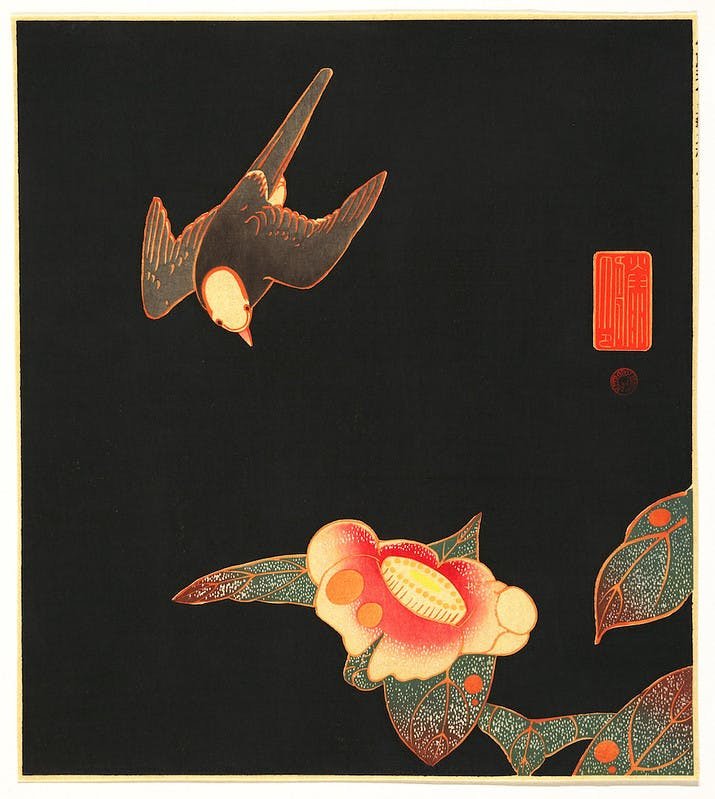

In his Art and Scholasticism, the French Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain writes about art as an invitation to behold, to look and in so doing, to love. He describes art as an impulse to say what needs to be said. Often, I think we are trying to point out—like bells being rung at the consecration—that we really need to pay attention to and witness the sacramental, miraculous, beautiful and mysterious that are always present in the world. When we view a painting or listen to a musician’s song, we are naturally curious to know about the person who created it. We try to discern some autobiography in the art, and often we do learn about the artist this way. This must also be true of God. I look at God’s artwork, His Creation to know Him. Observing fallen humanity, too, tells me about people—their longings, their loves, their lives.

Maritain says mystery exists where there is more to be known. This is why we can keep finding “more to be known” when we read or hear something again, look at a painting again, hear the same Gospel again, look at flowers again. There is something mysterious at work in it, which art tries to depict in a way that truly makes us see it. Many of the psalms begin with, “Sing to the Lord a new song.” How can we do this? Where there is more mystery to probe, there is always something new to see. This is what the Christian artist tries to do—to sing a new song.

Whatever I am choosing to do, for whatever reasons, the fact is that I am giving it my time and attention. In the 2017 film “Lady Bird,” directed by Greta Gerwig, a nun who teaches at the Catholic school where Lady Bird attends says to her, “It is clear that you love Sacramento.” Lady Bird responds, somewhat irritated, “I guess I pay attention.” The nun, Sister Sarah, replies, “Don’t you think they’re the same thing? Love and attention?” She is quite right. What I spend my time on, then, shows me what I love. Jesus said, “By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35). What we love, then—that to which we give our attention—will mark an artist as Christian. What we love and freely choose.

So—why study English? Why write? Why follow Jesus or practice faith? The same reason that I sat beside the radiator on those early mornings, reading. The same reason that I chose a career path whose prospects are … not the most lucrative. Love. Love. Love. Not infatuation—love. I might not enjoy working a particular job, staying up late when it’s the only time I have to write, being frustrated by the nonlinear process of writing, or being charitable to someone who is difficult, but love—the true kind that draws my soul upward—compels me to do these things.

This love involves, sometimes, choosing a path that does not make perfect sense. A path that risks something. Maybe risks everything. Sometimes this seems foolish. Reckless. Naïve.

But at least I love what I do.

Mary Grace Mangano is a poet, writer, and professor. Her poetry has been published in Ekstasis, Literary Matters, Mezzo Cammin, and The Windhover, among others, and her essays and reviews appear in places such as Plough, Comment, and America. She received a 2025 Individual Artist Finalist award from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts and lives in New Jersey.

"Risk is the price of love, and love is the point of life."

Thank you for sharing this guest post. So many gems to mine in this piece. Excited to find those hiding in "The Locust Years"!

This resonated with me so much. I want to write my own response because I have a large family with multiple disabilities, and I am panicked at my ability to support my children. If it were a matter of my own poverty I would do what I love, but with children who will likely never leave the home I have to think in longer financial terms. To what extent does doing what one loves become irresponsible? I pray and God does not give clear answers.