Dear friend,

As an undergraduate, one of my favorite courses was a one-off seminar class on Herman Melville, in which we read, over the course of a semester, all of his published works. While I’d read both Moby Dick and Billy Budd at that point in my young life, it was a totally different prospect to dive into all of Melville, whose themes of desolation and consolation were at once so absolutely iconic and so absolutely American. While not all of his work was remotely worth reading (with Pierre: or, The Ambiguities seeming particularly unfortunate), Melville was the key that, for me, bridged the great questions of the Classical tradition with the great dilemmas of the American continent and psyche. I am still thinking about Melville; he will be relevant for the remainder of my life. Like the ocean, one can swim and fish in him, but one could never exhaust the depths.

In that spirit, I am so pleased to bring you this special guest post today from the excellent C.W. Howell, a historian and writer. His upcoming first book, Designer Science: A History of Intelligent Design in America, will be published in Fall 2025 by NYU Press, and his work has featured in Wired, Scientific American, and Plough. He holds a PhD in Religion from Duke University and an MTS from Duke Divinity School. He lives in North Carolina with his wife, Mary Carol, and writes regularly about religion, science, and technology on his website www.cwhowell.com. He also links his essays to his substack, to which you should subscribe (link down below).

Today, C.W. helps re-introduce us to Lewis Mumford, a man who helped bring the work of an underappreciated “regional” writer named Herman Melville into America’s national canon, helping cement his status as one of our major writers, and of possibly the only true American epic—Moby Dick. Mumford, a philosopher of design, found in Melville the same sort of darkness and enlightenment that so captured me, and which are only becoming more relevant as our culture, like a one-legged whaler, continues to strike from the depths.

Enjoy,

- Paul

We live in dark times.

Though, one might argue, doesn’t it always seem that way to those who peek their head up from their work to gaze upon the state of the world?

Jump back 150 years, and you’ll find Herman Melville lamenting the rotten heart that pulsed beneath what he called “snivelization.” His pessimism radiates through his work. The average American is a “confidence man,” and Christendom is comprised of nothing but nations slavishly devoted to Mammon.

Melville’s despair was augmented by his writing career, which seemingly went nowhere but down after the success of his first book Typee. It may be a classic now, but Moby-Dick simply baffled in its day. After his novel Pierre failed, Melville was perceived to be “crazy” by the literary establishment. He spent his waning days as a customs inspector, writing Billy Budd in his spare time—but leaving it unpublished at the time of his death.

Now, Melville is in the American canon. How did this rapid reversal come about?

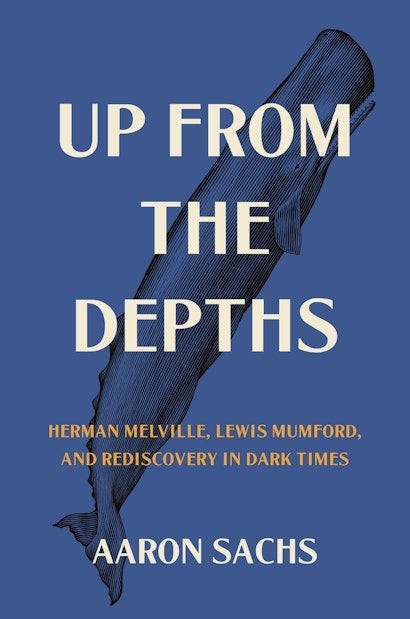

As Aaron Sachs chronicles in Up from the Depths, his recent dual biography of Herman Melville and Lewis Mumford, no small role was played by the now almost-forgotten Mumford. As a young man, he wrote the second-ever biography of Melville, and was the first reader to take Melville’s work after Moby-Dick seriously.

Melville baptized Mumford’s intellect and imagination, for all its good and ill. Melville gave him a lens through which to see the world—its glory, beauty, and majesty, but always with concurrent darkness, depravity, and horror. It was one of Mumford’s greatest achievements that he helped inaugurate the Melville revival and place him at the center of American letters.

One can’t help but remark on the irony, however, that Mumford is now as obscure as Melville was. Sachs wrote his book because he felt that we are in dire need of reviving Mumford too, and that he can fortify us to meet the challenges of our very own dark times.

Who was Lewis Mumford?

Mumford was well-known in his day, even appearing in TIME magazine in 1938. His writing still surfaces in contemporary books on technology or the environment. But he has faded from view, an error that I hope books like Sachs’s or Eugene McCarraher’s The Enchantments of Mammon might rectify, as both attempt to recover the man’s perspective.

His work is difficult to categorize, as his oeuvre touched on every part of human history and seemingly every avenue of human thought. Throughout his long life (1895 – 1990), he wrote prolifically on the history and philosophy of technology, he helped found environmental studies as a field, he was the architecture critic for The New Yorker for forty years, and he was a literary scholar who wrote on utopianism and (of course) Melville.

But Mumford hardly fulfilled the stereotype of the elite academic. He formed his dour worldview while he was in the navy during World War I, and most of his learning came self-taught—he attended college but never received a degree beyond a high school diploma. Always feeling like an outsider, he left the New York City of his birth and found refuge living in rural Amenia, NY.

His capacious learning, omnivorous interests, and ferocious writing style defy easy labels. Americans of either conservative or liberal bent are apt to find things to love and hate in him, and his own writing strikes a curious fusion which sounds equal parts Russell Kirk and Frantz Fanon.

On the conservative-sounding side, he disdained modernity and valorized the Middle Ages. The medieval period, he felt, was a time of entrenched spirit and (maybe ironically) a deep humanism. Its God-centric society became, by an interesting logical extension, anthropocentric—but in a good way, because it fostered the human spirit.

In contrast, he scorned western civilization and its imperialism, colonialism, and capitalism. He demanded racial reparations and constantly drew attention to the virtues and achievements of indigenous peoples. He was one of the world’s leading antifascists during World War II and was accused of communist sympathies in the 1950s. He was convinced that, as Sachs writes, “fascism is an outgrowth of the exploitation inherent in industrial capitalism—which means that antifascism must consist [quoting from Mumford’s Faith for Living] ‘in part in offsetting the debilitating effects of our too mechanized environment and our too impassive routine’.” Our machine-centric world is the breeding ground of authoritarianism, surveillance, and the erosion of democracy. To save what is good in our world, we must resist the machine.

In my view, one of Mumford chief ideas, that of the megamachine, is helpful in not only understanding our contemporary serfdom to mechanized civilization, but where such a thing came from, what threat it poses to democracy, and how it was defeated once before.

The Megamachine

In his earliest and perhaps still best-known work, 1933’s Technics and Civilization, Mumford sketched out some of the key features of machine civilization as he saw it. There is, in such a society, “contempt for any other mode of life or form of expression except that associated with the machine.” We created a “walking abstraction: the Economic Man.” These “successful neurotics looked upon the arts as unmanly forms of escape from work and business enterprise.”

As Mumford wrote in The Condition of Man, what modernity did was add a new category to the good, the true, and the beautiful: “the useful.” This wouldn’t necessarily have been horrible on its own, but it eventually became a “total replacement.” The useful wasn’t a good, it was the only good. And the machine has very specific ideas about what counts as useful. We have reconstituted ourselves, then, as robots, as “Organization Men.” The Organization Man, he wrote in The Pentagon of Power, is “that part of the human personality whose further potentialities for life and growth have been suppressed for the purpose of controlling the fractional energies that are left, and feeding them into a mechanically ordered collective system.” Almost all of us feel the burden and pressure of integrating and living in this system.

Mumford described such a mechanical collective as the megamachine.

In the late 60s and early 70s, Mumford wrote a duology called The Myth of the Machine, in which he revisited and expanded his perspective on machine civilization. Instead of focusing only on the modern period, he embarked upon a massive history of humanity from the pre-historic to the present, and he concluded that not only is machine culture dominant in the present, but it had been in the bronze age too. This goes against our expectations. We tend, after all, to equate machinery with all the gears and cogs and pistons of the industrial revolution—or perhaps the silicon and transistors of the computer age. But for Mumford, this is too simple. The machine is bigger, older, and more pervasive than that.

The megamachine, he argued, is not simply a construct, a mechanical device, or a digital fabrication. It was not just oil and gears or chips and silicone. It was more—it was a system. It existed in the ancient world just as much as in the modern.

In Volume 1 of this duology (entitled Technics and Human Development), Mumford explained that the megamachine actually predated advanced technology. It was joined at the hip with the idea of divine kingship, and it was typified by the pyramids. These were constructions that required enormous manpower and the kind of rigorous accounting and proceduralism that characterized bronze age civilizations. They were created with only primitive technology and without much animal power beyond that of “mechanized men.” This was its true machinery. Every person involved was part of a vast conglomerate, a mechanical collective composed of gears and cogs. But these cogs were organic. They were humans. They were us.

The megamachine, both ancient and modern, militates against human life. And so, Mumford’s great cause was, as Eugene McCarraher called it, the “gospel of life.”

The Cause of Life

In The Pentagon of Power, Mumford explained the difference in his approach to history. “In defiance of contemporary dogma,” he wrote, “[I] did not regard scientific discovery and technological invention as the sole object of human existence; for I have taken life itself to be the primary phenomenon, and creativity, rather than the ‘conquest of nature,’ as the ultimate criterion of man’s biological and cultural success.”

Mumford detested the common conception that humans are different from animals because of our use of tools (the old homo faber notion). Plenty of animals use tools, he argued. Such ability doesn’t make us unique. What’s different about us, he wrote in Technics and Human Development, is that our tools can become “modified by linguistic symbols, esthetic designs, and socially transmitted knowledge.” It is our brains, not our hands, that are distinct. And it is language that makes this possible—our greatest invention and achievement.

Mumford emphasized that “man is pre-eminently a mind-making, self-mastering, and self-designing animal.” The best societies were the ones that were animated by human focuses, ones that prioritized human experience and life.

Mumford manifestly did not believe that technology was innately bad or corrupting. His response was not rejection but interrogation. No technology, as Neil Postman would also remind us, is neutral. It always has a purpose, agenda, and telos. We must then repeatedly ask the question: who is served by our technology? Is it humanity? Or the machine? And the answer is, unfortunately, quite often the latter—at the frequent expense of the former.

Work is a good. We must not eliminate it. As he contended in in Technics and Civilization, “the chief benefit the rational use of the machine promises is certainly not the elimination of work...[it is] the elimination of servile work or slavery: the types of work that deform the body, cramp the mind, deaden the spirit.” Unfortunately, the machine does not prioritize human flourishing but its own, and this undercuts all our creative endeavors and life-giving work. “Creative activity,” he wrote, “is finally the only important business of mankind.” Our primary economic, social, and political goal should be “to produce a state in which creation will be a common fact in all experience: in which no group will be denied.”

This priority is partly why Mumford valorized the Middle Ages so much, even though he was not a “trad” in the manner that our terminally online nostalgics tend to be. What he saw was that the medievals were more in touch with human feeling than we are. They had an omnipresent sacred art and fully developed human feeling. Their cathedrals testified to their breathtaking view of the cosmos. Even if the Church was often a haven for hypocrisy, it couldn’t fully kill this underlying beauty. No Western society, he wrote in The Condition of Man, had been “more completely dominated by respect for the spirit” as theirs was.

Mumford even saw the persistent myth of the “Dark Ages” as conspiratorial effort to block us moderns from learning anything useful or fulfilling from that period of history. This anguished him, as the architecture critic in him especially valued the medieval city as the archetypal form of human co-existence. Would that we could rebuild our cities to serve human needs rather than the automobile (which has since 1900, he pointed out in The Pentagon of Power, “slaughtered vastly more human beings than have been killed in all the wars ever bought by the United States”).

What Is To Be Done?

But we can’t “go back” (furthermore, we shouldn’t want to). So, what do we do?

It’s easy to give in to despair, but Mumford resisted this tendency. He likewise rejected atavistic calls to “retvrn” to traditional religion as a solution—though that’s not to say Christianity didn’t inform his blueprint for resistance to machine civilization.

After all, we cannot understand our present without our Christian past. “If we are to find a straighter path,” he wrote in The Condition of Man, “we must at least recognize the historic reasons for Christianity’s success.”

Life was on the Christian side, and it triumphed in the conflict of religions and philosophies of the late antique world because it offered an unbridled hope. It prevailed “not because the Christians had better reason than the pagans to hope for a renewed world, but precisely because their unbounded hopes defied reason…Only those who believed in the impossible were prepared to carry on in this dying society.”

That said, Christianity inadvertently paved the way for the megamachine’s recrudescence. It tolerated and then bowed before capitalism, allowed its own ethic to degrade and the Sabbath to fall out of practice, and it failed to adequately resist fascism. Christianity also, as Mumford argued in Technics and Civilization, helped inculcate the rational and calculating approach to modern life that became the basis of capitalist economics (something Mumford rather controversially suggested began in the Christian monasteries with the development of the clock). In The Pentagon of Power, he lamented that Christianity failed to incorporate its radical ideas fully into a political order, and its “reluctance to come to grips with slavery and war and class exploitation” meant that it eventually was responsible for its own loss of respect and authority.

Because of this, Mumford was suspicious of institutional religion, even though (as Sachs points out) he held great respect for Christianity’s ideals. It’s telling, however, that he struggled and to conceive of an alternative to Christianity for an imaginative solution. He could not fail but to simply reproduce Christian language when he was grasping for a weapon with which to fight back. We needed, he wrote, to be “born again.” “To Mumford,” writes Sachs, “the rediscovery of a humanist Christianity entailed recognizing that that our values must constantly be reborn.” He wanted to recover the Sabbath and to cultivate humility. In the end, he had no choice but to default to Christian categories. There was nowhere else for him to go.

Though his work is often bleak, Mumford concluded his last great work (The Pentagon of Power) with a dose of optimism and a call to action. Detaching from the system might be easier than we think. We can turn off. We can “do nothing” (in the words of Jenny Odell). The choice, in the end, might be ours. “For those of us who have thrown off the myth of the machine,” he wrote, “the next move is ours: for the gates of the technocratic prison will open automatically, despite their rusty ancient hinges, as soon as we choose to walk out.”

The subtitle of Aaron Sachs’s dual biography of Mumford and Melville is Rediscovery in Dark Times.

Just as Mumford recovered Melville, we should recover Mumford. He can help us think critically and in depth, not only about technology, but our history and our religious views too. His perspective can help us to think things from a fresh angle and to start to make the unthinkable thinkable—that is, how to survive and thrive in a world that prioritizes the machine over the human.

It’s happened before, and it can happen again. No one, argued Mumford, could have predicted Augustine’s dissenting attack on Roman society. But what was unthinkable because the standard story after The City of God. Augustine can provide an example to us now, too. “If such renunciation and detachment could begin in the proud Roman Empire, it can take place anywhere, even here and now.” After all, only those who believe in the impossible are capable of carrying on.

Perhaps we, too, should follow his example. There may be a way out of the wreckage. Ishmael survived the sinking of the Pequod; Melville survived because of Mumford. And, as Sachs wrote in his effort to recover Mumford, “one resilient survivor is enough to revive a civilization, to keep the story going.”

C.W. Howell is a historian and writer. His upcoming first book, Designer Science: A History of Intelligent Design in America, will be published in Fall 2025 by NYU Press, and his work has featured in Wired, Scientific American, and Plough. He holds a PhD in Religion from Duke University and an MTS from Duke Divinity School. He lives in North Carolina with his wife, Mary Carol, and writes regularly about religion, science, and technology on his website www.cwhowell.com. He also links his essays to his substack, to which you should subscribe:

Extremely informative, and bracingly well written, Paul; thanks for sharing!