I am so pleased to share this guest post from Jeff Young, a dear friend, brilliant poet, and New Orleans gourmand. Jeff draws our attention to our attention, which in the paradoxical way such things seem to work, both guides and is guided by us.

-Paul

“You are what you eat, from your head down to your feet,” is the opening line of a health PSA jingle that ran between cartoons on Saturday mornings in the 1970s. It was a catchy tune, one that still gets stuck in my head from time to time. And, anatomically, its message is true.

Our bodies assimilate the food we ingest. If we want to be healthy, we need to eat healthy foods. Given our current health crisis in the United States (the alarming rates of diabetes, heart disease, etc.), perhaps we need to bring this PSA back. But I have recently been imagining another version of this PSA, a version that would urge us to have healthy souls. The first line would go something like this: “You become what you see.” Or, perhaps better: “You become what you behold.” That message is true, too.

Human beings are born imitators. Despite our best intentions, we tend to grow up to be much like our parents. This trait that we have—to become what we see—is why businesses spend billions of dollars in advertising each year. It’s why a brand will pay big bucks to have their products placed in movies. It’s why famous musicians, football players, and gymnasts are paid handsomely to promote brands. It’s why Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram utilize “infinite scroll” in their apps. There is something about our ability to see—and the way we choose to use that ability—that influences who we are and who we become.

I remember when I first learned to ride a motorcycle. I practiced and practiced and practiced. At first, I rode around the block. After a few days of that, I moved on to touring through the neighborhood. A few days later I ventured further out. I was determined to do it right. I did not want to end up in a hospital or morgue. After practicing for a couple of weeks, I signed up for a two-day safety course. One bit of wisdom our instructor said over and over again was this: Look where you want to go. On a bike or a motorcycle, your arms and those two wheels are going to take you where your eyes are pointing.

Life, it turns out, works the same way.

This idea is nothing new. It is part of the wisdom of Western civilization that has been handed down for millennia. But it is wisdom that we seem to have forgotten or have chosen to disregard. In today’s world of sensory overload, a world in which one can scarcely escape the overabundant presence of screens, a world filled with noise and every manner of auditory and visual distraction, it is imperative that we recover this wisdom. Imperative, that is, if we want to recover the health of our souls.

From the times of the ancient Greek philosophers, we have been urged to see the connection between sight and moral education, which is also thought of as growth in virtue or living “the good life.” We are not moralizing in that, at least not a negative morality that only presents prohibitions. Rather, we are talking about what we are to actively and joyfully do (how we are to live) in order to become good. This positive action is to begin to live the good life. And it starts with where we are looking.

To catch a glimpse of this wisdom, let us look at key insights from two of Plato’s works: Symposium and Phaedrus. In Plato’s Symposium we watch as Socrates does what Socrates does best: he pulls at his companions’ stated belief or conviction until the underlying assumptions unravel, revealing the heart of the central question they are discussing. In this case, Socrates is among friends at a dinner party and they are discussing the nature of love (Eros). The climax comes as Socrates recounts a conversation he had with Diotima, a woman of Mantinea whom Socrates holds in great esteem. It is she who Socrates credits for teaching him the art of love. She explains to Socrates that love is “a great spirit,” a daimon, noting that “everything spiritual… is between god and mortal.” Using myth, she establishes with Socrates that love is what drives us to seek wisdom, beauty, and immortality. Love drives us to seek the good.

In walking through these ideas with Socrates, Diotima goes on to elucidate what some refer to as “the Ladder of Love” or “the Soul’s Upward Journey,” which is the journey of the individual soul from the sensual to the spiritual, a journey of growth in virtue, of growth in love. For Diotima (and for Socrates), the lover desires to see and to possess the beloved. This possession is more than just a physical possession. It may be more accurate to think of it as a spiritual possession, as a union of persons. In a certain sense we can say that the lover desires to become the beloved. As Diotima explains, for the lover at the start of the journey, the beloved will be another particular human person. But on this journey the “beloved” can become all human persons, all souls, all knowledge, and—eventually—beauty itself. Diotima’s ladder, the upward journey of the soul, shows us that, ultimately, love desires to see and to possess—to become—Beauty, to see and to become the Good.

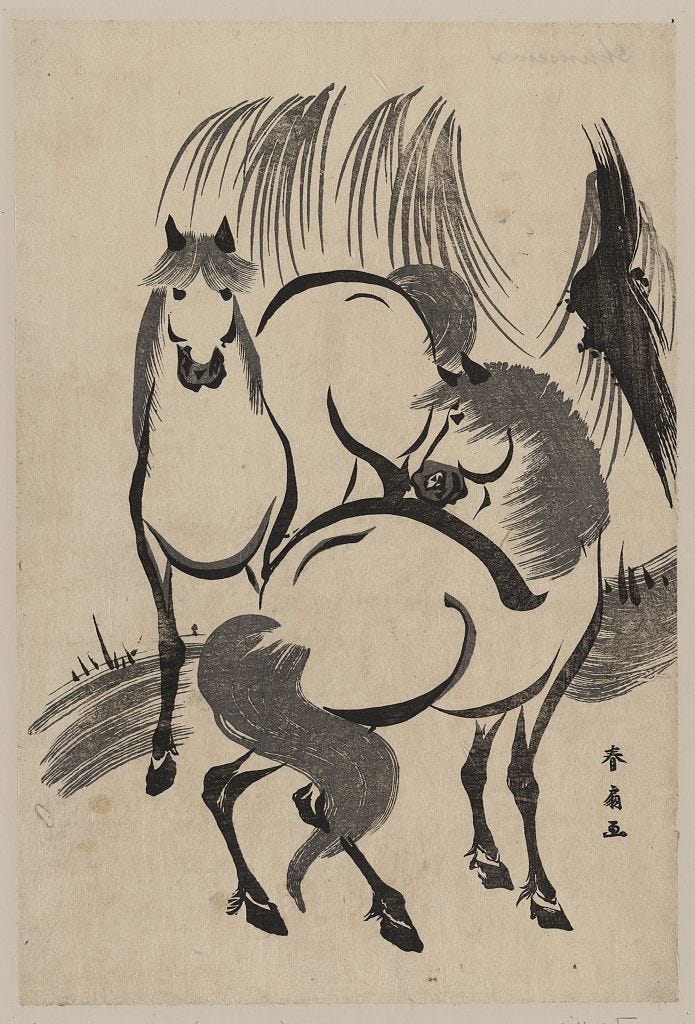

In Phaedrus, Plato gives us the striking image of the soul as a charioteer trying to control two horses: one unruly and wild, the other tame. But before that, Socrates introduces the idea of the Palinode, and he gives an example to show us that there is a connection between the proper understanding of love and seeing properly. After both Phaedrus and Socrates have given speeches on Eros, Socrates acknowledges that they were both on the verge of impiety towards the gods, and he sets out to “take it back” and “make it right” through a new speech or poem (which is a known as a Palinode). The example he gives is of Stesichorus who lost his sight after speaking ill of Helen. After composing a Palinode, Stesichorus immediately regained his sight. This short interlude that Socrates gives us should not go unnoticed. From it we learn that we can only see clearly when we love rightly. He then proceeds to compose his own Palinode to Love, in which he offers the image of the soul as a charioteer.

As a metaphor this image is fairly easy to understand. Each of us can look at our own lives to see the metaphor “in living color,” so to speak. “Let us then liken the soul to the natural union of a team of winged horses and their charioteer,” Socrates says. Since we have one horse that “is beautiful and good and from stock of the same sort,” and another (unlike the gods) that “is the opposite and has the opposite sort of bloodline… chariot-driving in our case is inevitably a painfully difficult business.”

So far, so good. Reason, the charioteer, has at least one horse on his side. And don’t we all have our good sides? Don’t we all have traits that help us along in life and make us good citizens? At least most of the time? But, there’s another horse, one that is passionate, irascible, strong-willed. A horse that wants its own way. A horse that doesn’t always play well with others. And don’t we all struggle with a horse that is something like that? But, here’s another question: why do the horses in this example have wings?

The reason for the wings gets us closer to our central concern—that we become what we behold. In Socrates’ palinode the charioteer with his horses (if their wings grow strong through nourishment by being in close proximity to true, good, and beautiful things) is caught up in the great procession of the gods led by Zeus. The procession swirls through the cosmos to “the high tier at the rim of heaven.” Most of us can’t make it that high because of our bad horse.

But what draws us to the high tier? Why do we long to see the rim of heaven and beyond? “The reason there is so much eagerness to see the plain where truth stands is that this pasture has the grass that is the right food for the best part of the soul, and it is the nature of the wings that lift up the soul to be nourished by it.” Here we discover what it is all about. Diotima’s ladder, the upward journey of the soul, is all for this: to see the True, the Good, and the Beautiful and thereby possess It (or be possessed by It). Or, to express it slightly differently (as my spiritual tradition would say): to become one with It.

Our ability to see shapes who we become. This is about more than just imitating our parents or being influenced by visual advertising. Our sight enables us to see true, good, and beautiful things, which lead us toward the True, the Good, and the Beautiful. By beholding those things we grow our souls, we grow in virtue, and we can become good.

If what Diotima and Socrates say is true—about love, about beauty, about the soul—that we become what we behold, then my task is to do what my motorcycle instructor drilled into me.

I need to look where I want to go.

Jeff Young writes and resides in Covington, Louisiana with his wife and four children. He is the author of Around the Table with the Catholic Foodie: Middle Eastern Cuisine (Liguori Publications, 2014).He can be found at CatholicFoodie.com.

The title of this is perfect and oh so true.

A lovely reflection. One of the great themes of the Symposium is that our desires somehow reveal ourselves--and attention can be a way of reflecting on (and maybe better aiming?) our desires.