Dear friends,

Today’s post is intended to be read as the beginning of a practical portion of my short foundational dispatches here at The Rose Fire. If you have been following along, we have considered the inner natura of things in “The Inconsolable Secret,” the danger of that inner capacitiy of attention and relationship in “The Hunger of the Dark,” and began to introduce the idea that beauty is what purges and strengthens that inner capacity of soul in “Into the Fire.”

In each of these, my goal has been to try to offer a shared understanding about some of the large, but usually unseen, element of our inner lives, our world, and the true stakes of all of it. I now would like us to turn our attention to some of the specific ways that these notions of soul and beauty touches our daily lives. We will first do this by considering two vital portions of the human lifespan that are uniquely threatened by consumer society; Elderhood and Childhood.

I am considering the latter before the former because, in my view, the grief associated with the loss of true Elderhood is more universal than that associated with the loss of true Childhood, and naming that grief is the place to begin. As you read, I hope that you consider, peaceably, your own personal relationship to this: perhaps there is gratitude that comes of it all for you. Perhaps there is grief. Both seem healthy to me.

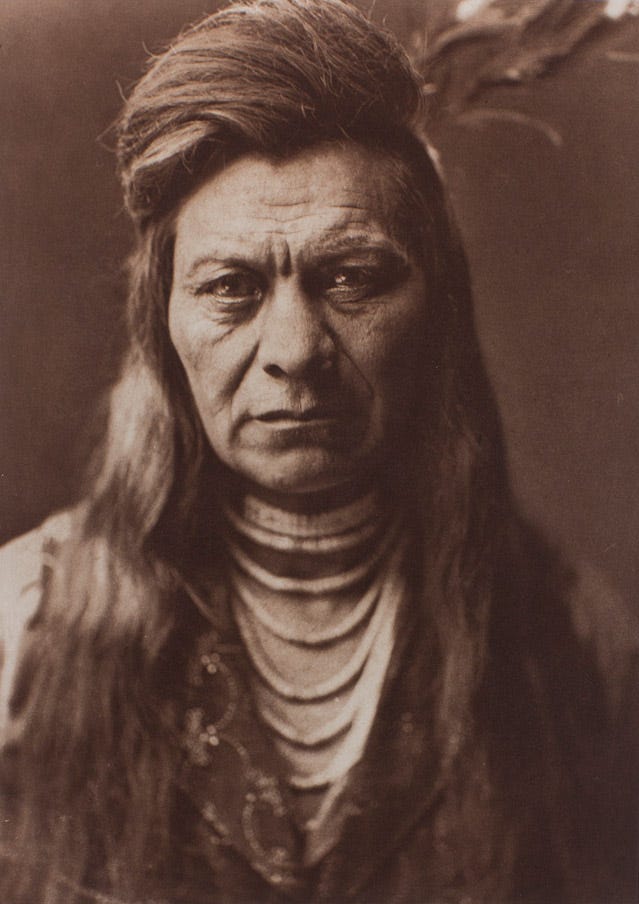

I considered many images to open this, but could not find one better than Black Eagle’s below (despite Edward Curtis’s occasional romanticizing of Native life for Eastern American viewers). It is the eyes. Everything I am trying to say here I can see held in Black Eagle’s eyes.

Look, for a while, at his eyes.

-Paul

The natural world is full of many rhythms. Most are cyclical; the earth goes round the sun, the moon goes round the earth. Some are cycles within cycles, in the manner of certain clocks, whose hands sweep through hours, through minutes, and through seconds off the same internal gears; the cicadas sleep for seven years within the cycle of the earth and sun. When the earth is warmed, having reached the right proximity to the bright star, they wake, unable to explain, and sing their life into the warm night. And of course, the stars that prick the sky above them are marking, in their way, the vast eons.

Some rhythms are tidal: rather than going round they go up and down. They ebb and flow. Such action follows the logic of the wave. There are progressions and regressions. The water washes high for a time, and then recedes. It is low. Then it begins to rush in again. Like the cicada, I suppose that the tide could not tell you of the distant influence whose power gathered and dispersed it. What wave could tell you properly of the moon that pulled it?

We live in a time that seems to be experiencing a notable deficit of wisdom. I can only compare it to the things I have read in books, or the stories of the older people I have known. It is tempting for some people to point out that every age feels something similar. (Socrates, you will remember, in Plato’s Phaedrus lamented the advent of reading with similar fervor to those now lamenting its decline.) And I am too young, perhaps, to start whining about any of it, being not yet forty.

And yet it strikes me, as I try to survey this time honestly, that history may be like a beach, and that some qualities of human culture have a tidal rhythm too. They rise and recede. We can note, accurately, that they were once higher than they are now. We can see why certain boats are beached in the receding of that water, unable to sail or fish. We can think, and act accordingly. And it seems to me that wisdom is ebbing.

What is wisdom? Among other thing, it is that quality of perception which shapes good judgement. Wisdom discerns things soundly, with the result of practice. To be wise is to know how life works; to understand the ways of things, and then to let the life be shaped by understanding. Wisdom can be put in books, but it does not come from books. It comes from watching. From seeing.

There is an inescapable quality of experience that is present in wisdom. The Wise Man or Woman is not always correct, but their way is correct. They are not right in every individual instance or opinion, but their life is right.

Because of this quality of experience, traditionally the domain of wisdom is reserved for the aged, and extra respect is accorded to those who have lived for many years. This logic makes sense of course. To survive, particularly in the difficulties of the pre-Modern ages, was not always an easy task. People died. They died young, and they died often. There were fewer shock absorbers in the world. Stupidity or folly could not be solved with a 911 call or a co-pay. To make it into old age with one’s life and sanity intact said a bit more about one then.

Of course, that inescapable quality of experience does not have to be one’s own experience. As one personal example among many, for the past three generations, Pastor men have religiously closed the curtains of the house at dusk, in order to take away the tactical advantage of anyone who may be looking from outside into the brightly-lit interior. This was a habit which my grandfather brought back from the villages of France as he slowly fought his way through them in 1944. It is a sort of wisdom, I suppose, a habit born of a specific experience and passed along. It is not mine, but it has become mine, and I keep it. Perhaps our line will one day benefit from it. Who can say?

This is, maybe, a poor example. No matter. You see the idea. The wisdom of others may be passed along. We may keep what seems useful, but we will not always be able to tell what is useful. Wisdom, in its particular forms, is a living thing. It is a conversation between generations. It is, forever, in need of tending and of attention. Like any tradition, it lives only as long as it is loved, and it is loved only as long as it is kept.

In this way, the concept of the Elder has been central to nearly every culture throughout history. Some societies have given great thought and form to organizing and empowering their Elders, but many have had the luxury of simply taking it for granted that the more aged among them would be, actively keeping wisdom.

By keeping, I don’t just mean to retain. Rather, I mean keeping in the way that a beekeeper keeps her bees. Does she own the bees? One would be foolish to apply such a crass word to that relationship. She keeps them. She provides a place for them to dwell; she provides space, safety, and the type of care that allows them to flourish. In return, their unique life enriches hers. She may benefit from them, may even profit nicely. But there is a sacred stewardship that is more than economic, at least ideally, in the situation. To reduce it to transaction would be to cheapen something glorious and free.

There have been many particular ways that human societies have organized their Elders, but in general, they have been granted the honor to serve in matters of discernment and decision. To name what a situation really is, and to say what people ought to do about it. In a healthy culture, they serve in various types of guiding and initiatory functions: it is a bishop who alone is able to confirm the young in the Christian liturgical traditions, it is the elder of the tribe who says when it is time for the young man to go through the traditional rites, it is grandma or auntie whom you go to for advice or hard truths in that situation that is tormenting you.

To be an Elder is not merely to be an Older. It is inhabit a role that is larger than yourself, to take up a simple and basic human trust. One can be an Elder alone, but such a situation is naturally rare. Think instead of the old men gathering on the porch, of the kitchen full of Church Ladies. Think of the aunties, spread throughout time as a wonderful and fearsome company of joyous meddling and cookery. Think of the uncles, with their chainsaws and socket wrenches and endless stories that you heard before. Think, maybe, of the Iroquois, whose elder women were “the soul of all councils,” according to Joseph-François Lafitau1, dispersing food and goods, electing male chiefs to the Grand Council, and who were the final arbiters of peace and war. It was this model of ideal eldership (imperfect though it was) that formed some inspiration for the model of that Republic which would arise on the same continent, and under whose governance I presently live.

It is easy to find examples of this from traditional tribal societies worldwide, whose scale and humanity encourage the intentional development of Elders. But of course this is a human reality. “It will out,” like Hopkins’ “shining from shook foil.” We may, even in the collapse of the structures for this in consumer society (more on that below), rejoice and be grateful for those people who have managed to become not merely Olders, but Elders, to the enrichment of all of us.

But I am delaying the real point, for as a culture we seem, as I have said, to be experiencing a notable deficit of wisdom, that very quality which Elders are to keep. And Elders, like that tide, seem to be also at an ebb. The keeping has not been well kept. The keepers have not been either. And we suffer as a result.

But first, what makes an Elder?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to THE ROSE FIRE to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.